Alejandro Amor, the former owner-CEO of for-profit FastTrain College, is scheduled to face a jury trial in Miami Wednesday morning. Amor and his co-defendant, former FastTrain admissions staffer Anthony Mincey, face criminal

charges of defrauding the federal government to obtain about $6.5 million in student aid -- Pell grants and Direct Loans.

Two other FastTrain employees charged in the case,

Jose Gonzalez and

Michael Grubbs, already have

pledguilty and are on the

government's witness list.

Amor and FastTrain gained

national attention in late 2014 when federal and state prosecutors alleged in court papers that the school "purposely hired attractive women and sometimes exotic dancers and encouraged them to dress provocatively while they recruited young men in neighborhoods to attend FastTrain." (

Republic Report reported about this FastTrain marketing strategy back in May 2012.)

Gonzalez told investigators that Amor had told him to "hire the sluttiest girls he could find." Gonzalez said he responded, according to a witness summary, "that he was a Christian man and did not know how to hire those kinds of women." Accordingly, a helpful FastTrain colleague, Juan Arreola, turned up "with three women who he said were recruited from Miami area strip clubs who now worked as admissions representatives" for FastTrain. "They all wore short skirts and stiletto heels.... ARREOLA routinely told female admissions representatives at all the campuses to wear shorter skirts and higher heels to help enrollment numbers. ARREOLA also took the women to area homeless shelters to help recruit ineligible students."

But while the stripper angle excited the Internet, the actual offense for which Amor is on trial is something less flashy, but still quite abusive: The school allegedly enrolled some 1,300 students who had no high school degree or other eligibility to receive federal aid, and then simply lied to the government, representing the new students as high school graduates, with fraudulent diplomas from places like Cornerstone Christian Academy. FastTrain also allegedly misled its students, telling them a high school diploma was not needed, or that they could earn one while attending the college. Other students allegedly were coached to say they were high school grads.

Confronted by investigators several years ago, Gonzalez agreed to wear a wire, and recorded

this conversation with Mincey:

Gonzalez: Let's just say my estimation is that FastTrain has about 700 students. I would say 400 don't even have a diploma, bro.

Mincey: Mm-hmm, that's a fact.

In a separate civil

whistleblower lawsuit against Amor that has been joined by the U.S. Justice Department and Florida attorney general Pam Bondi (R), former FastTrain admissions officer Juan Peña alleged that the company's "business model is to enroll as many students as possible in order to become the beneficiary of more federal funding.... Many of these students do not read or understand English [and] cannot write their own name."

If convicted of carrying out this fraudulent scheme, Amor faces up to five years in prison. (While I and others have sometimes criticized the Department of Education for

lax enforcement of its own regulations aimed at curbing for-profit college abuses, investigators from the Department's Inspector General's office deserve credit for building this case.)

Amor used his income from FastTrain to help finance a lavish lifestyle, as

pictures that

Republic Report harvested last year from Facebook suggested -- Caribbean vacations, $2 million waterfront home, a 54-foot yacht called "Big One," a private plane.

FastTrain, founded in 1999, operated campuses in the Florida communities of Miami, Plantation, Tampa, Jacksonville, Pembroke Pines and Clearwater.

Like many for-profit college owners, whose schools often receive nearly 90 percent of their funding from federal aid, Amor made friends with politicians -- at least before the FBI raided its campuses in 2012. He built

especially strong ties to U.S. Representative Alcee Hastings (D-FL), one of the biggest defenders of for-profit colleges on Capitol Hill and a

big recipient of the industry's campaign cash. Amor gave contributions not only to Hastings, but also to Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL), former Florida Governor Charlie Crist (R-I-D-whatever), and the Florida Republican Party.

FastTrain, until it ceased operations, was also a

member of APSCU, the for-profit colleges' lobbying group, which

continues today to use your tax dollars to press Congress -- and to hire expensive lawyers to try to convince a federal appeals court -- to overturn Obama Administration regulations aimed at curbing the kinds of abuses that have occurred at FastTrain and other predatory companies.

For more than a decade, bad actors, large and small, in the for-profit college industry have used a

toxic mix of deceptive marketing, high-pressure recruiting, astronomical prices, low spending on instruction, and false reporting to authorities to rake in tens of billions in federal tax dollars, ripping off taxpayers and ruining the financial futures of countless students.

The industry all told has received up to $33 billion a year in federal student aid.

Federal and state law enforcement is finally catching up with these scams, with

major investigations of big industry players like EDMC, University of Phoenix, ITT Tech, Kaplan, DeVry, Bridgepoint, and Career Education Corp. But while these probes of for-profit colleges have proliferated in recent years, most are civil, rather than criminal.

Corinthian Colleges, one of the

worst actors in the sector, collapsed after the Department of Education imposed financial sanctions, amid

fraud investigations by at least 20 states and four federal agencies. The company, which was getting as much as $1.46 billion a year in taxpayer money, has filed for

bankruptcy and claims it has no money to pay back its creditors or any of the students it abused.

Where did all the money go, and what is the personal responsibility of executives like CEO

Jack Massimino, who was taking in more than $3 million a year?

Amor's trial, if it goes forward Wednesday, will be the only one of its kind in recent memory.

Federal prosecutors have filed criminal charges against a handful of other for-profit college officials. Those cases have led to guilty pleas before any trial could occur. Last fall, Doyle Brent Sheets, 58, the former president of Texas-based American Commercial College, was

sentenced by a federal judge to two years in prison, fined $5000, and ordered to pay almost $1 million in restitution for stealing federal student aid; his school was fined another $1.2 million. Staff members of Baltimore's All-State Career School

pled guilty last year to comparable offenses.

In 2009 and 2010, three top executives of

Vatterott College pled guilty to a criminal conspiracy to fraudulently obtain federal student grants and loans for ineligible students in 2005-06 by providing false general equivalency diplomas (GEDs) and doctoring financial aid forms.

The similarity of the Vatterrott crimes to those charged against FastTrain show that the lure of huge federal financial dollars can spur unscrupulous acts at companies owned by operators from all walks of life, from the Miami entrepreneur behind FastTrain to the Wall Street owners of Vatterott, which was owned from 2003 to 2009 by the New York-based private equity firm

Wellspring Capital Management and since then by a larger Boston-based private equity firm,

TA Associates. (One investor in TA and Vatterott is

Mitt Romney.)

Given the powerful evidence of fraud at numerous for-profit colleges, Amor's criminal case should be the start of a major effort to hold personally accountable the operators of institutions that have broken the law.

*** The imperative of making individuals accountable was underscored late Monday, as the Department of Education passed on an opportunity to take decisive action against an institution, ITT Tech, which has consistently demonstrated both predatory behavior and financial irresponsibility. The Department, in a

letter to ITT, found repeated failure by ITT to meet its fiduciary obligations and account for federal student aid.

ITT is also

under investigation or being sued for deceptive practices and fraud by 19 of our nation's 50 state attorneys general, plus the U.S. Department of Justice, Securities and Exchange Commission, and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) said last night that ITT, "deemed 'not financially responsible' by the U.S. Department of Education, continues to receive billions in federal Title IV dollars." He added, "Isn't it time to protect students and taxpayers and turn out the lights at ITT?"

But instead of declaring a 21-day delay on the receipt of federal money, as the Department did when finding similar misconduct at Corinthian, or even a 30-day delay, which ITT's conduct surely warranted, the Department imposed a 10-day lag, which may prevent ITT's immediate collapse. The Department also could have, but did not, impose a freeze on new student enrollments.

It may be that ITT will soon fall of its own weight anyway. But it again appears that the Department, under Secretary Arne Duncan, is unwilling, post-Corinthian, to take responsibility for pushing another big for-profit to the brink.

Unfortunately, continuing to send federal taxpayer dollars -- and thus more students -- to predatory schools will only create a bigger bailout mess than the one the Department already faces.

This post also appears on Republic Report. -- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Ty Morse is the CEO of Songwhale, an interactive technology company focusing on enterprise SMS solutions and Direct Response campaigns, both domestic and international.

Ty Morse is the CEO of Songwhale, an interactive technology company focusing on enterprise SMS solutions and Direct Response campaigns, both domestic and international.

Wheeeeee, what fun!

Wheeeeee, what fun!

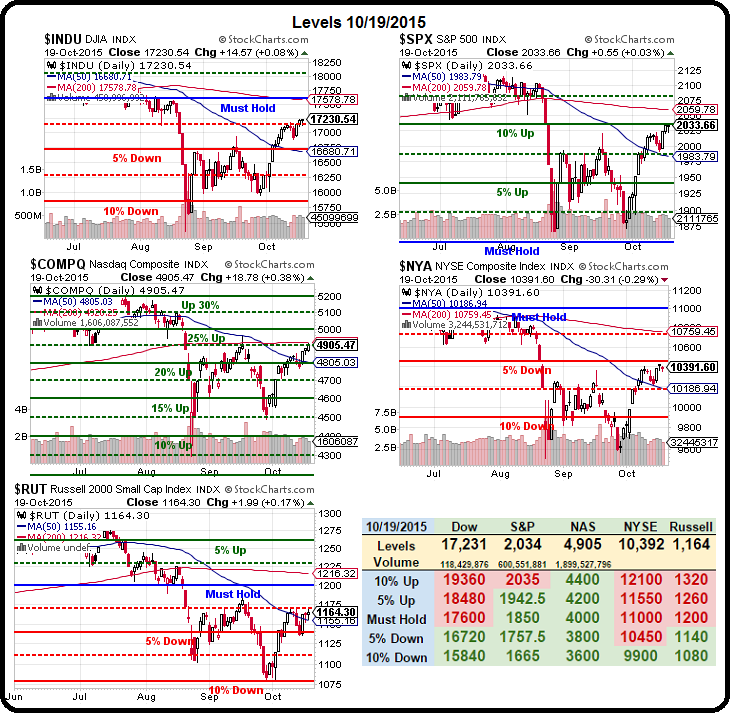

.jpg) While we are waiting for market clarity, we've been cashing in on our Futures trades. In last week's Live Trading Webinar, we went long on Natural Gas (UNG) Futures (/NG) and this morning we closed out our /NGX5 (Nov) contracts at goal and let our Dec contracts ride. As you can see, we did quite well with the trade but we're expecting to do even better on the December contracts - now trading at $2.68 off our $2.6515 entry. Our goal is $3, so that's still 0.32 to go at $100 per penny, per contract if all goes well.

While we are waiting for market clarity, we've been cashing in on our Futures trades. In last week's Live Trading Webinar, we went long on Natural Gas (UNG) Futures (/NG) and this morning we closed out our /NGX5 (Nov) contracts at goal and let our Dec contracts ride. As you can see, we did quite well with the trade but we're expecting to do even better on the December contracts - now trading at $2.68 off our $2.6515 entry. Our goal is $3, so that's still 0.32 to go at $100 per penny, per contract if all goes well.  I'm sorry I don't have specific trades for the cheapskate readers but it's earnings season and we don't to free trades during earnings season. Don't worry though, in late November we'll be happy to give away some more free trade ideas so don't sign up or you might get ideas like these from last weeks' Morning Posts (and no, I'm not leaving out bad ones - go check!):

I'm sorry I don't have specific trades for the cheapskate readers but it's earnings season and we don't to free trades during earnings season. Don't worry though, in late November we'll be happy to give away some more free trade ideas so don't sign up or you might get ideas like these from last weeks' Morning Posts (and no, I'm not leaving out bad ones - go check!):.jpg) That takes us back to our

That takes us back to our